Affordable housing is serious business

Featured Members

Where you live may be the single most important factor in your financial and social wellbeing. Your rent or mortgage dominates your personal budget, your location determines the jobs you might have, and your neighborhood influences the quality of schools your children attend.

Affordable housing and well-developed communities are the bedrock of a thriving society and economy. Beyond the benefits of shelter and stability, a home is a tangible asset that can drive upward social mobility. Council Steward Stacey Epperson, CEO of housing development nonprofit Next Step Network and a 30-year veteran of the housing industry, has seen first-hand how owning a home can be a steppingstone on the path to greater economic participation in the United States.

“Homeownership lifts people out of poverty, or it helps them take the next step into the middle class. It breaks generational poverty. It remains one of the best determinants of wealth creation and equity creation for a family,” she says. “A loan based on your home’s equity can help you put your kids through college, as it did for me. Research shows better education outcomes, reduced use of government assistance, and better health outcomes – particularly for people with asthma – among people who own homes.”

But, not all Americans have the same opportunities to benefit from homeownership. Millions of households — particularly in lower-income communities, communities of color, and immigrant communities — have effectively been barred from home ownership by historical exclusionary housing policies and their legacies leading to a chronic lack of affordable housing on the market in United States.

Across many major cities, the availability of affordable housing is reaching a crisis point. New homes are not coming onto the market at prices that most Americans can afford. In 2022, the average price of a single-family house was double the mortgage value that an average American family could afford. Rented apartments are more commonly available, but rising rents and stagnant wage growth have put those once-affordable space beyond many peoples’ budgets.

To make up the difference, the United States government supports 10.2 million citizens with rent assistance. The Housing Choice Voucher Program – also called “Section 8” referring to the portion of the U.S. Housing Act of 1937 that established it – allows individuals and families to choose a place to live and have the government cover much of the rent. Demand for these vouchers is at an all-time high, and families may wait years on a local waitlist to receive a voucher. And yet once they have it, there is no guarantee they will find somewhere to live. Affordable units – even with rent assistance – are scarce and sometimes have waitlists of their own. Landlords in most of the U.S. are not required to accept tenants paying with vouchers, and they may decline rental applications from voucher holders. So, despite housing assistance programs, nearly 600,000 people experienced homelessness in January 2022.

Over the last five decades as the U.S. population has grown, housing development simply hasn’t kept up. Every year since 1974, the nation built fewer homes than needed to satisfy demand. Builders were constructing just one home for every five new families looking for one in 2009, at the peak of the financial crisis. And only 10 percent of those built were of a size and price that would make them available to first-time or low-income buyers.

Next Step’s Epperson describes a housing market that isn’t friendly to entry-level homebuilders: “In many cities across the country, we’ve made it difficult to get approvals from local governments to build new housing because of issues with zoning or permitting to build. Many builders left the marketplace in the housing crash in the United States around 2008, and then COVID made that worse. The builders who are still working must build a more expensive home to meet the margins they need to stay in business. Particularly during COVID we’ve seen spikes and supply chain issues that continue to make it more expensive.”

Growing demand for affordable housing without growing supply has led to steeply rising rents and home prices, pushing many consumers out of the ownership market and away from the economic doors it can open. The COVID-19 pandemic also changed patterns in demand for housing, deepening market pressures as many Americans desired to leave the country’s largest and most crowded cities for homes with more square footage and outdoor access.

The bottom of the market is crowded. Despite greater market demand at lower price-points, supply has not kept pace. Many people who already live in entry-level housing cannot afford to move up to the next tier, monopolizing the small existing affordable housing stock. And for others, rising property taxes and flat wages are turning once-affordable homes into financial burdens. Some choose to shoulder the cost, others must look for affordable options farther and farther from the places where they work, learn, and shop. Various agencies estimate the U.S. is missing somewhere between 3.8 and 6.8 million appropriately priced houses and apartment units needed to maintain a healthy housing ecosystem and the economy that rests atop it.

Where affordable housing can be found, it often comes at the cost of long commutes to work and school, higher cost of travel, and lack of essential services like healthcare, childcare, and grocery stores. Poorer communities trade their quality of life for marginally lower rents and mortgages.

Space for Hope

The U.S. affordable housing market is not without hope. Businesses are working to build higher-quality, more affordable housing to bring place-based economic opportunity more equitably to Americans.

Next Step Network is pursuing energy-efficient, factory-built homes as a sustainable homeownership solution. Also called “modular” or “prefabricated” housing, these houses are constructed in sections and transported to a property for final fitting. They are built to standardized specifications and use efficient labor and materials to reduce the cost of the home, making factory assembly a competitive way to create affordable homes and maintain a healthy business bottom line. Today’s modular homes come in a wide variety of sizes and designs and carry the same level of craftsmanship and quality materials as traditional site-built homes.

It wasn’t always this way. In the United States, mobile home trailers are the most common form of manufactured housing. They have a poor reputation – often rightly deserved – for flimsy quality and losing their market value over time. Several million people in the U.S. live in housing of this kind built in the 1970s. Fifty years on, these homes can be burdens rather than assets to their owners.

“As I was getting my start with the manufactured housing market, I had an elderly lady approach me about retrofitting her mobile home,” shares Next Step CEO Epperson. “It was beginning to fall apart. For the cost, it was better to replace than to repair. As we began to plan her new home, I was shocked to learn she was paying at least half of her $1,000 monthly income for utilities in her current mobile unit. That’s how inefficient the house was.”

“When we got her new home in place, her bills dropped so dramatically from the improvement in energy efficiency that the utility company sent someone to investigate. They feared something had happened to the homeowner! When they learned who had built the new home on the property, the utility company CEO invited me to her office and said, ‘I don’t know what you did, but I need you to do it a lot more.’”

Epperson’s early-career lesson that it matters not only how you build, but what you build has shaped Next Step Network’s focus on working with home manufacturers to adopt heightened standards for quality and energy use. Every building specification the organization provides is Energy Star rated and designed for a long-lasting home that appreciates in value. Collaborating with manufacturing facilities across the country, they are spreading elevated practices widely.

Next Step is currently working with Pennsylvania-based Eagle River Homes to manufacture 241 homes for the new Kilpatrick Woods subdivision in Hagerstown, Maryland, and collaborating with longtime building partner Clayton Homes, a Berkshire Hathaway company, to develop a new program to help housing developers engage with factory-built housing as a resource.

Innovating for Economic Inclusion

In Atlanta, housing startup Mākhers Studio also manufactures homes, but aims its solutions at the most vulnerable segments of the housing market, including individuals and families experiencing homelessness, aging adults, college students, military veterans, and people displaced by natural disasters.

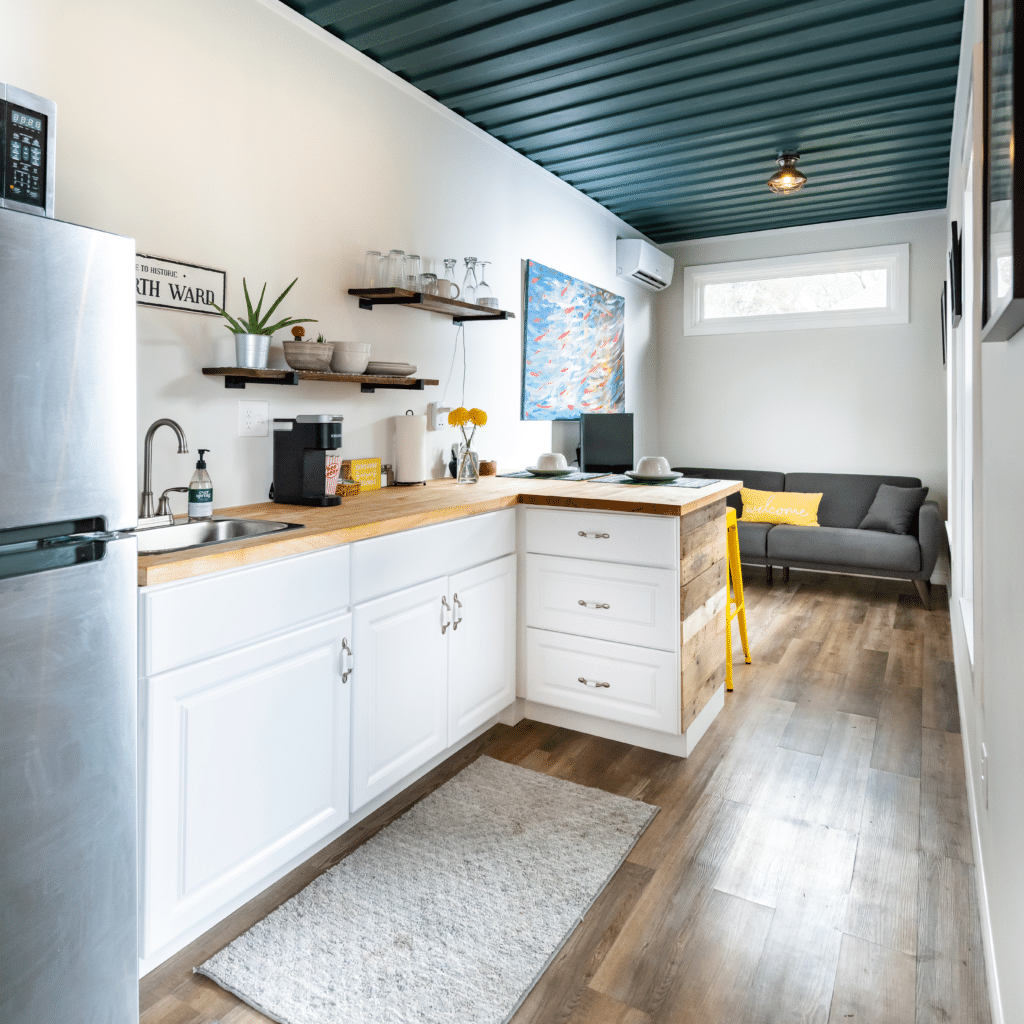

Led by founder and CEO Wanona Satcher, the company is pioneering a design-and-build approach to retrofit metal shipping containers into small footprint, flexible-use “pods.” The metal containers offer an abundant material that is easily repurposed by adding interior walls, electricity, and plumbing. Since they’re designed for shipping in the first place, the finished pods are easy to send wherever they are needed. Retrofitted housing pods provide a foothold on the first rung of the social mobility ladder, offering safety and stability that residents can build a life upon.

Mākhers’ most popular housing pod design, pictured below, is built from a typical 40-foot container and features a single bedroom, a bathroom with a walk-in shower, a kitchen with eat-in countertops, and a living room. Other designs include two-bedroom models, pop-up office and retail spaces, classrooms, and mobile health clinics.

As in most real estate markets in the United States, Atlanta housing development vies with lack of land zoned for new development and high prices on what is available. Mākhers Studio’s install-anywhere pods may prove to be a breakthrough.

“If you look at reimagining spaces, you start to find there’s lots of space available to really make a difference.” CEO Wanona Satcher says. “There are lots of alleys and vacant or blighted properties that aren’t suitable for traditional development. We can revitalize those spaces with small structures like our modular units.”

“Because our pod footprints are small, we can fit near bus stations or transit stations. Low-income people often have to choose between paying rent and paying for transit to get to work or paying for groceries. If we can put our spaces where they don’t have to make that choice, we are meeting the needs of people, planet, and profit.”

Bringing housing closer to services is a particular passion area for Satcher, an Atlanta native. She recalls taking two buses to get to and from school every day.

“It’s part of the reason for what I do now to understand, redefine, and redevelop the built environment so that it is equitable, so that kids in the future can grow up in places where there is easy access to community services, especially education and medical care. To do that, we have to have affordability, we have to have housing available to those families, specifically in underserved and under-resourced black and brown and indigenous communities.”

For Stacher and Mākhers Studio, place-based equity extends beyond the design of their spaces into a deeply local approach to all aspects of their operations and workforce strategies. Rather than work in a several-hundred square foot factory outside of town, Mākhers Studio seeds smaller “micro factories” within communities that need their services most. They strategically hire skilled workers from nearby neighborhoods as an invitation to participate in the transformation of their community.

“I don’t like to use the word empower because I think we each have our own power,” says Satcher. “What I like to talk about is to inspire people to find and use that power. Our goal is to create micro-manufacturing facilities so that you can design with local input, build locally, hire locally, and deploy locally.”

We Need a Strong Solution Ecosystem

Businesses are finding unique ways to equitably satisfy the market demand for more affordable housing. The solutions, however, cannot come to fruition from the company’s efforts alone. Governments, financiers, housing developers, nonprofits, and advocates all have a role to play to create a housing ecosystem that welcomes new development.

Construction and community development are controlled primarily by city governments. For affordable housing to be built, the city must grant construction permission and work with the builder to set guidelines for the final building. Zoning codes – which determine what kinds of buildings are allowed and where – often present a challenge.

“Zoning for new affordable housing has to change,” says Next Step’s Epperson. “Right now, single family manufactured housing is zoned out of most cities. We can’t build it without an exception to the rules or a change to the local codes. Both options take time.”

Next Step Network has been working with a development partner and the city government of Harrisonburg, Virginia for more than two years to get permission to build 1,000 affordable homes, 100 of which will be Next Step-certified, single-family factory-built houses.

After a long collaboration, the zoning board gave unanimous approval for the project. But then the project hit a snag at the City Council. At the meeting where the project would be finalized, advocates and “not-in-my-backyard” opposition carried on a debate until past two in the morning. At the next meeting, the project passed by one vote.

“That’s how close it comes in being able to do our work,” says Epperson. “We need resources to continue the up-front zoning battles and the community education to increase acceptance of new affordable housing. All this work is local.”

Local policy can either deter or incubate innovations, as Mākhers Studio knows. In early 2023, they worked with two nonprofit organizations in Durham, North Carolina to design and build a micro-community for veteran residents and their families. Mākhers added five housing pods, a central courtyard, and an edible garden to enhance an existing property of several duplex homes. Known in the housing industry as additional or accessory dwelling units (ADUs), small add-on homes like these are an attractive option for affordable housing development.

For homeowners who fear losing their home to rising property taxes or cost of living, they offer extra income from rent as well as an affordable living space for someone in need. ADUs also increase the population density of a neighborhood, which can be a boon to local businesses.

Despite this, they are illegal in most cities, either expressly banned by city zoning laws or disallowed by default because they don’t meet local construction code requirements, such as minimum square footage for standalone residences or mandatory parking spaces. Some communities, like Durham and Atlanta, are revising local laws to enable creative solutions.

Builders are still working to overcome economic challenges to re-enter the housing construction market to provide affordable homes. “One of the largest obstacles we have is access to patient, flexible capital or mezzanine equity that’s willing to take more risk,” says Epperson.

Large low-rent apartment buildings are much easier to build, says Epperson, because that segment of the industry has created the “perfect capital stack” of federal and local tax incentives, construction capital, investors, and developers that make the buildings possible. Although apartments address the direst housing needs, they lack the generational wealth-building benefits owning a home can provide.

“We need to find a way to replicate that in the single-family marketplace. There is a tax credit for single family production that has been introduced at the national government level. If that is passed, it would make this easier.”

Mākhers Studio finds capital by engaging individuals, fellow businesses, nonprofits, and other organizations in their customer base.

“Social enterprise has to be adaptive. Everything is dynamic: people are dynamic, conversations are dynamic, environment is dynamic. How can we best position ourselves to adapt to those changing needs efficiently so that the work that we do scales sustainably? The only way for us to be successful is collaboration, sometimes with larger institutions you might not think of as traditional housing partners.”

Satcher is currently in talks with doctors and attorneys to envision on-site housing at a local hospital for postpartum care for women who may have difficulty traveling between home and the hospital for treatment. She also has ideas for hospital-owned housing for homeless patients.

“We’re literally meeting people where they are and bringing unique value to those institutions who don’t have resources in-house to think creatively about how to solve the problem,” she said.

Building a Better Tomorrow

An abundance of affordable housing supports place-based economic revival, racial equity, and a better standard of living for all. It can only succeed with the voice of business in the mix. As industry experts, businesses can bring new innovations to the market at an enterprise scale more efficiently than anyone else. They can help communities identify paths forward.

Epperson urges businesses to share their expertise with the public: “There are grassroots people out here that are trying to make change. And while we are committed, we are under resourced when it comes to corporate participation in this policy-making arena. Let’s bring everyone to the table so we can make this positive change.”

Business doesn’t operate in a silo; it can define the system in which it operates. That impact should be a purposeful one, Satcher adds. “Business at its best creates new systems around empathy and that empathy creates the capacity and efficacy for others to succeed. My purpose is to create new systems based on what we deem to be of value, and inclusivity.”

Hear more from Stacey Epperson and Wanona Satcher in our podcast story series.

- Listen Now: Epperson describes how public-private partnerships are helping Next Step Network bring high quality green to communities across the U.S.

- Listen Now: Satcher shares why Mākhers Studio is focused on hiring women and recent immigrants as community builders.